CSBIO Research

Genetic interactions

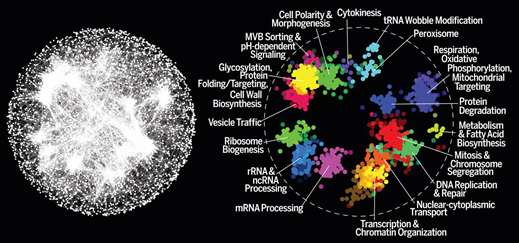

We are developing computational methods for mapping and interpreting large-scale genetic interaction networks in yeast and in human cells. A powerful approach to characterizing functional organization of genomes is combinatorial genetic perturbation. While the disruption of individual genes only rarely leads to strong phenotypes (e.g. only ~10% of the genome is essential in human cells), simultaneous disruption of combinations of genes can often result in interpretable phenotypes. These instances, where combined disruption or mutation of two genes leads to an unexpected phenotype, are called genetic interactions. Because of its genetic tractability and a rich set of existing experimental tools, yeast is the premier model system for analysis of genetic interactions. Working with the Boone and Andrews labs, we are developing computational methods for mapping and analyzing global genetic interaction networks in yeast. We have recently completed the first complete genetic interaction network for any species (Costanzo 2016) and are currently focused on mapping genetic interactions across diverse environmental conditions.

Genetic interaction analysis in human cells

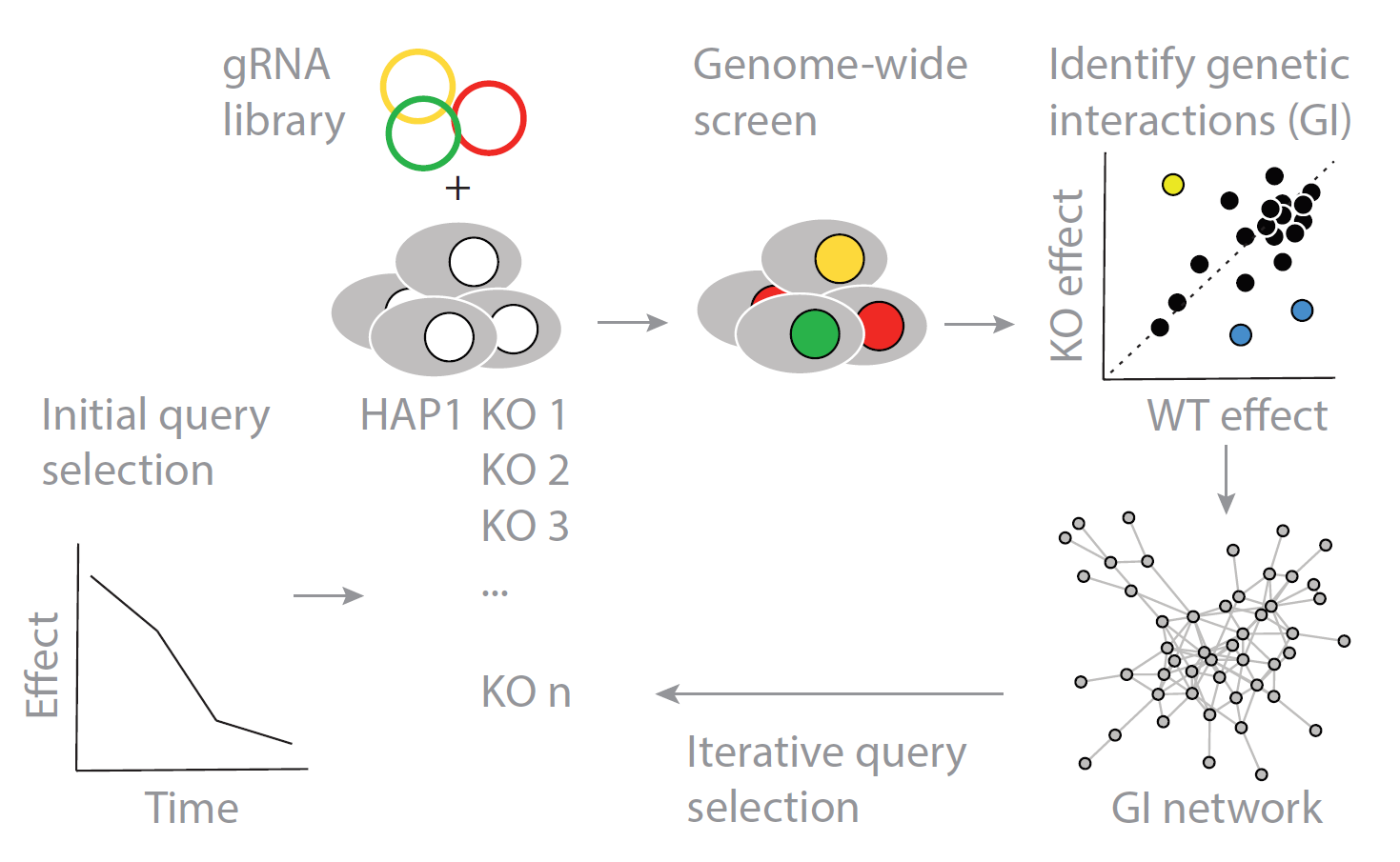

We work towards a global reference map of human gene function. In model organisms, genetic interaction mapping and network analysis can elucidate the function for every gene in the genome. Together with the Moffat, Boone and Andrews labs at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research in Toronto, we generate a genome-wide map of genetic interactions in a human cell line. Using CRISPR/Cas9 screening, we test effects of simultaneous mutations in two genes across millions of gene pairs. To represent genetic interaction information of all possible ~180,000,000 combinations, we develop methods to predict and screen gene pairs that have the best chance of interacting. We also develop methods to identify genetic interactions from CRISPR/Cas9 screening data and integrate other genomic data to generate a global atlas of human gene function.

Genetic interactions in complex human diseases

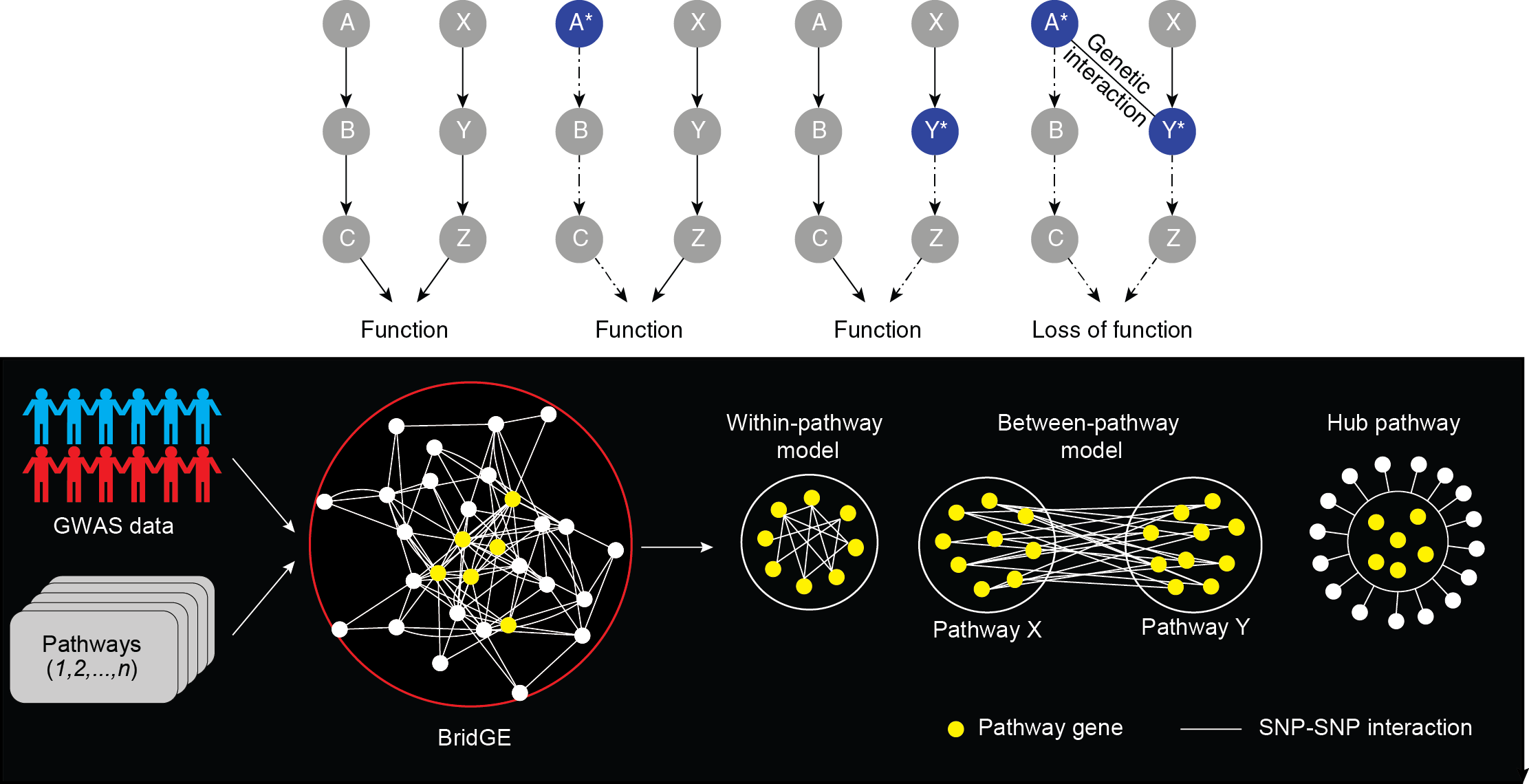

Almost all complex human diseases have a genetic component. Understanding how genetic variants contribute to the development of these diseases can be invaluable to our society. It can provide guidance to disease diagnosis, inform genetic-centric strategies for disease prevention, and stimulate the development of new and more effective drugs. Although our knowledge and understanding of the genetics that underlie complex diseases has advanced substantially in recent years, due to the complexity of most human diseases, the precise genetic causes of the large majority of diseases are still unclear. For instance, in most diseases, the discovered single genetic variants identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) only explain a small fraction of the estimated total heritable disease risk derived from familial aggregation studies, suggesting there are still genetic factors that are not well-understood. Genetic interactions have been reported to underlie phenotypes in a variety of systems, but the extent to which they contribute to complex disease in humans is significantly understudied. This is mainly because existing methods for identifying them focus on testing individual locus pairs, which undermines statistical power. We are working on leveraging insights from genetic interaction screens in model organism to develop methods to discover interactions from human population genetic data. More specifically, we developed a computational approach called BridGE that identifies pathways connected by genetic interactions from GWAS data. We examined this method with many complex human diseases and showed it can be used as a general framework for mapping complex genetic networks underlying human disease from genome-wide genotype data.

Modeling plant immune response

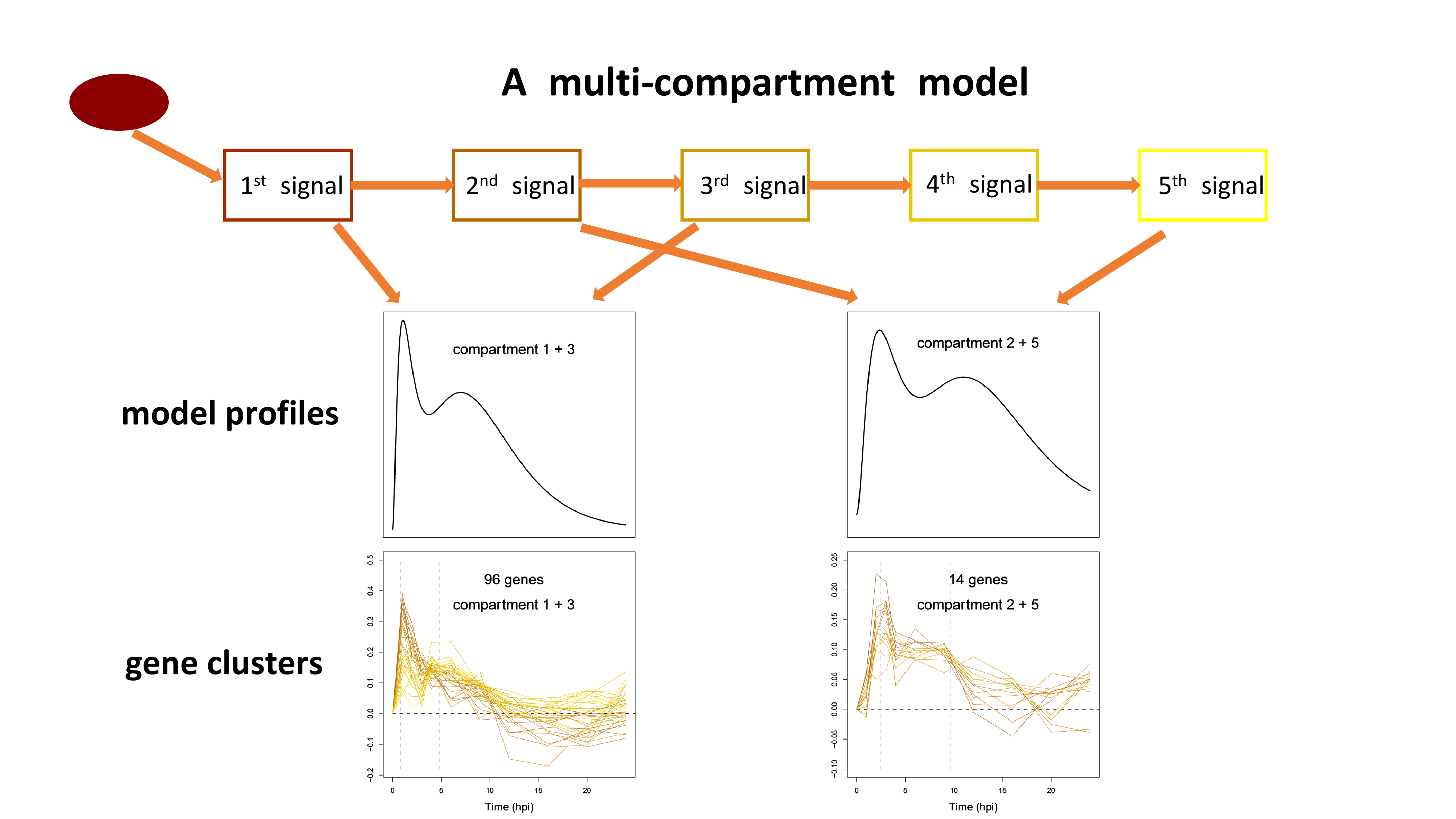

In collaboration with the Katagiri lab here at UMN, we are developing novel computational approaches to interpret dynamic transcriptome data in Arabidopsis generated during the plant’s immune response. Although clustering methods can help group genes based on the profile similarity, they fail to provide a mechanistic understanding of the gene clusters thus undermine the information within time-series data. In our research, we use multi-compartment models to generate dynamic profiles with fast and slow response patterns. Based on how well the time-series transcript data of a gene are fit, we can assign the gene to the compartment with the optimal response pattern. We find gene clusters enriched for transcription factor motifs that regulate early and late immune response. Our approach provides a mechanistic way to classify immune response genes and allows us to better interpret Arabidopsis transcriptome dynamics.

Chemical genomics

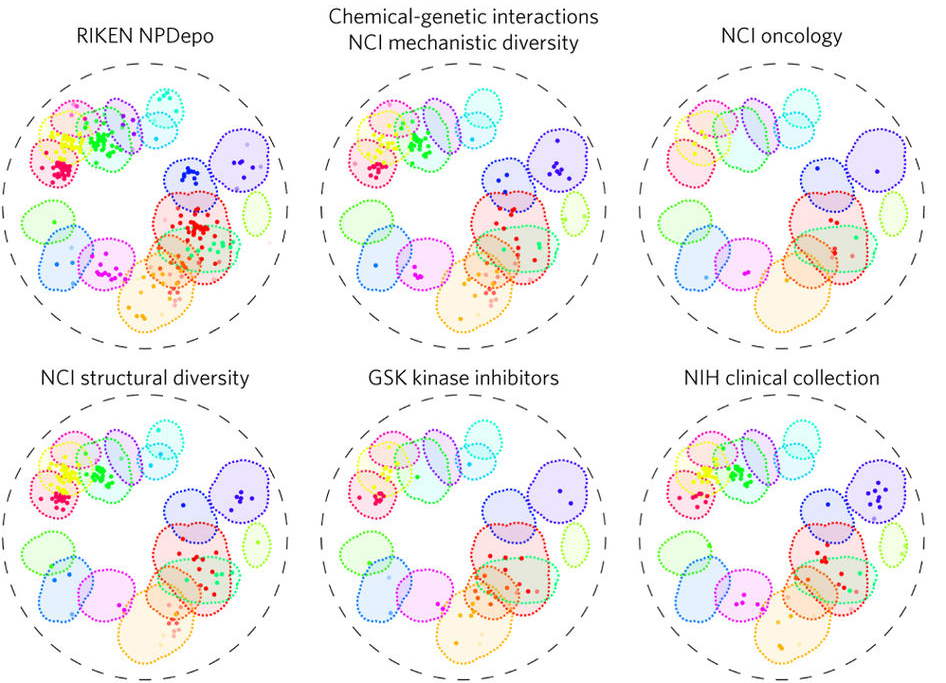

We are screening chemical libraries against the Saccharomyces Cerevisiae mutant collections in order to understand the mode-of-action of compounds. This research reduces the time and expense required for the creation of clinically relevant compounds. With our collaborators in the Boone Lab at the University of Toronto and at RIKEN in Japan, we have developed an ultra high-throughput chemical-genomics assay that allows the prediction of a compound’s gene- and process-level targets across the entire genome, filling a critical gap in the way compounds are screened for bioactivity. This methodology was applied to screen more than 13,000 compounds within yeast with diverse origins. From these data, we identified compounds with novel targets as well as the general cellular functions that tend to be disrupted by the compounds from diverse collections. In collaboration with the Bielinsky Lab, we are translating this chemical genomics work from yeast to human cells. CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables chemical-genetic screening in human cell lines, allowing us to interrogate chemical-genetic interactions across a library of defined deletion mutants. Current work focuses on developing analyses pipelines to identify chemical-genetic interactions and predict genetic targets or bioprocesses perturbed by a chemical compound. Using these screens, we can more efficiently identify candidate drug therapeutics and build a comprehensive drug library to help realize precision medicine.